When speaking of Catalan modernism, one of the images that comes to mind is that of the façade of Josep Puig i Cadafalch‘s Casa Amatller. Or the neighbouring cover of Casa Batlló, another masterpiece by Antoni Gaudí. And also the buildings of Lluís Domènech and Montaner such as the Hospital de Sant Pau.

It is well known that one of the pillars that sustain the appearance of these new constructions is that of the Catalan bourgeoisie. Industrialization produced a new bourgeois class, which was enriched by the creation of new and more competitive factories. But it often forgets another, more traditional sector that also made the Catalan bourgeoisie a lot of money: the landowners in charge of wine production.

We have to go back to the middle of the 19th century. The Mediterranean territories cultivated the vine with which they produced wine for their own consumption and traded with the surpluses. France was already one of the great wine centres, with wines of enormous international recognition.

But in 1863 a lethal plague arrived in the French vineyard: phylloxera. This small insect native to America destroyed most of France’s autochthonous vineyards in 1868. There was no wine in France, so he had to import wines from his neighbours, including Spain.

In addition, this productive crisis coincided in Spain with the increase of territories dedicated to the cultivation of vines and with an increase in the import of wines to Europe.

In Catalonia, the proximity to France made the traditional production centres the protagonists of the bottle trade. There were 15 years of economic expansion, in which French merchants came to Catalonia to buy wine. But these foreigners also invested in the improvement of Catalan infrastructures to facilitate transport; or they financially supported the landowners to increase productivity each year.

The economic boom caused many winery owners to devote part of their profits to other businesses, such as new industries. And they also took their real estate investment capital to Barcelona, a city that was growing incredibly fast on the orderly space of the Eixample.

Thus, money from wine production constituted seed money for new industries and was invested in the form of real estate. Thus the landowners consolidated themselves as a nascent bourgeoisie that would be in charge of promoting the architects and artists of Catalan modernism at the end of the 19th century.

In 1878 phylloxera arrived in Catalonia. By then, many winemakers had diversified their businesses and had settled in more urban areas, so they are not so affected by this crisis in their economy. Yes, some territories where the dependence on wine was more direct suffered from the phylloxera plague. In the Alt Penedès, for example, they got rid of this terrible insect at the end of the 19th century, initiating a new stage of economic progress that coincided with the peak of modernism. Architects such as Puig i Cadafalch, known for having built the Casa Amatller in Barcelona, built the Cavas Codorniú in Sant Sadurní d’Anoia. Other architects of Catalan modernism also intervened in the construction of other wineries.

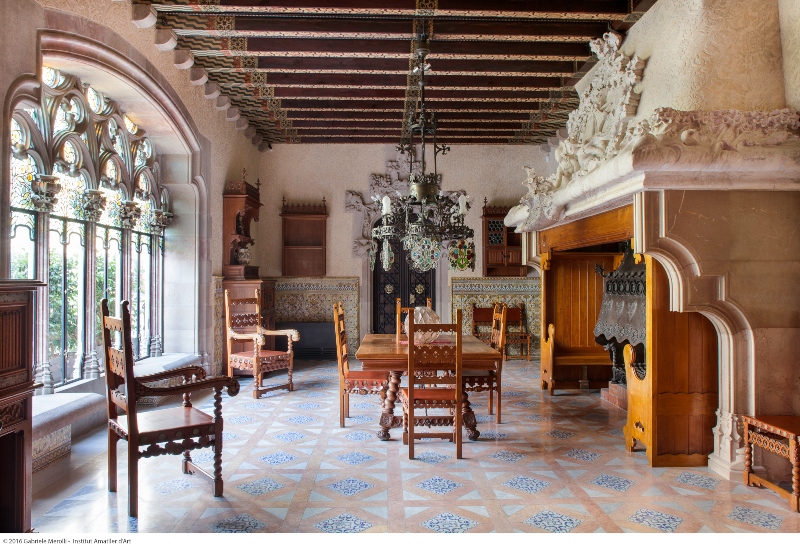

Therefore, Catalan wine and modernism are much more closely linked than they seem. So it’s a good idea to celebrate Casa Museu Amatller’s Modernist Nights with a glass of wine in its incredible surroundings. After a theatrical visit in which Teresa Amatller and her maiden propose a fascinating journey to a 1900 modernist house, is there a better ending than a delicious glass of wine?